In the schizophrenic gospel, God is both darkness and light. In the Christian gospel, there is no darkness in God (1 John 1:5), but God’s light reveals, contradicts and convicts our darkness.

The so-called double-bind theory was developed by Gregory Bateson in the 1950s as an explanation for schizophrenia. It explains how a certain kind of communication leads to a breakdown of personality, rendering the subject completely dependent upon the communicating authority.

“A double bind is an emotionally distressing dilemma in communication in which an individual (or group) receives two or more conflicting messages, in which one message negates the other. This creates a situation in

which a successful response to one message results in a failed response to the other (and vice versa), so that the person will be automatically wrong regardless of response. The double bind occurs when the person cannot confront the inherent dilemma, and therefore cannot resolve it or opt out of the situation. […] A double bind generally includes different levels of abstraction in orders of messages, and these messages can be stated or implicit within the context of the situation, or conveyed by tone of voice or body language. Further complications arise when frequent double binds are part of an ongoing relationship to which the person or group is committed.”

Double binds are a kind of paradoxes, but the contradictory statements are alwas on different logical levels, e.g. between the pragmatic and the linguistic. This makes the double bind hard to discover and rebuke (obvious self-contradictory statements would not be so). Examples of double-binds are:

“[…]a mother telling her child that she loves him or her, while at the same time turning away in disgust. (The words are socially acceptable; the body language is in conflict with it). The child doesn’t know how to respond to the conflict between the words and the body language and, because the child is dependent on the mother for basic needs, he or she is in a quandary. Small children have difficulty articulating contradictions verbally and can neither ignore them nor leave the relationship. Another example is when one is commanded to “be spontaneous”. The very command contradicts spontaneity, but it only becomes a double bind when one can neither ignore the command nor comment on the contradiction.”

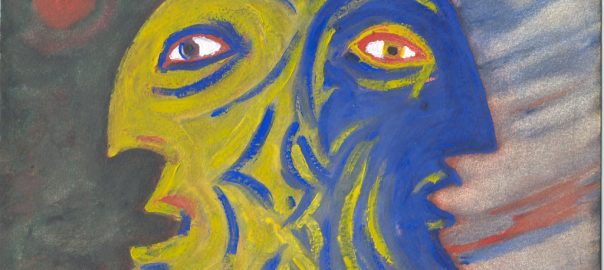

It is easy to point out apparent examples of double-bind communication in traditional evangelical rhetoric. For example, ‘not works, faith!’, or ‘God has paid the price himself, but you still have to believe!’ (where faith is considered something you do). Or ‘hate the sin, love the sinner’ (how do we distinguish?). Are these not paradoxes between the pragmatic and linguistic levels? Or what about this: ‘Yes, God is love, but he is also righteous!’. Or even worse: God loves you and will give you eternal life if you put faith in him. But if you don’t he will torture you in eternity as a punishment. The Father abhores you, the Son loves you. Jesus protects you from the Father. But they are one and have the same will. Such ‘yes, but’-theology paints a picture of a two-faced God, making us constantly oscillate between fear and thankfulness. This is what we, lacking a better term (suggestions?), could call the schizophrenic gospel (skhizein, σχίζειν, “to split”, and phrēn, φρήν, φρεν-, “mind”).

True and false paradoxes

One of the appealing things about the ‘schizophrenic gospel’ is that it seems to keep a firm grip on the paradoxical character of the Christian gospel. Not so: While it is obviously ‘paradoxical’, it’s paradoxality is different from that of the true gospel.

Rightly put, God’s judgment and salvation are two sides of the same coin, but this does not mean that God simultaneously hates and loves us. God does not judge because he is offended or vengeful, but because this is the way he saves his beloved creation.

The true dialectics of the Christian gospel is, that when we face the extreme limits of our existence, death, we come to know that we cannot save ourselves. This is where God reveals himself as our savior. The paradox is that we are brought to realize that God does not hate us, even if everything speaks against this truth. The paradox, which is really only a paradox from the perspective of ‘this world’, is that we have to die in order to live.

In the schizophrenic gospel, there is no real dying leading to true life. There is a dying of personality, alright, but only one that crumbles personality and makes it dependent upon some authority or other. The result is pietism, an infantile religiosity, mega churches full of sentimental pop-music, with an apparent liberty, that is, however, always contradicted by an authoritarian, legalistic morality.

In the schizophrenic gospel, God is both darkness and light. In the Christian gospel, there is no darkness in God (1 John 1:5), but God’s light reveals, contradicts and convicts our darkness. But by this conviction we die to our darkness, and are brought into the light of God’s love. When God out of love through his judgment and salvation in the death and resurrectionf Christ dissolves and reestablishes our personality (Barth), we are made whole and free persons.