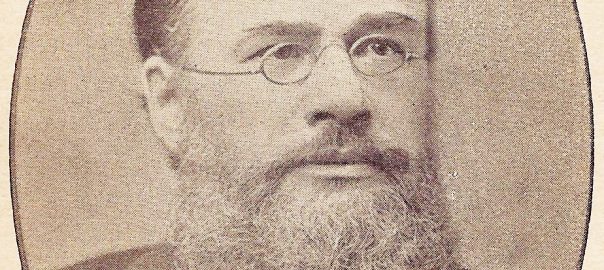

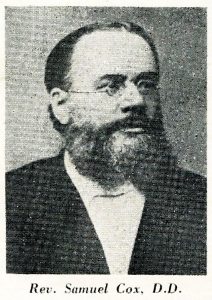

Samuel Cox was an English Baptist minister and writer, born near London. At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed at the London docks, where his father was employed. Having passed the exam at Stepney College he entered London University and in 1852 he became pastor of the Baptist chapel in St. Paul’s Square. From 1863 to 1888 he was a pastor at Mansfield Road Baptist chapel in Nottingham. Cox was president of the Baptist Association and received the degree of Doctor of Divinity from St Andrews University in 1882. From 1875-1884 he edited The Expositor.

In one of his perhaps best known books entitled Salvator Mundi: Or, Is Christ the Saviour of All Men?, a collection of lectures published in 1877, Samuel Cox argued that the popular notions of damnation, hell and eternity cannot be defended on the basis of Scripture. Cox defends the restorationist idea that post-mortem punishments are not retributive but restorative. Inspired by Andrew Jukes, he points out that the words in Scripture translated ‘eternity’, ‘eternal’ and ‘for ever’ does in fact mean ‘age’ or ‘age-enduring’ (p. 96ff, 117ff). Cox also argues that the words translated ‘damn’ do in most cases only mean ‘to judge’, so that no idea of eternal punishment can be derived from threats of damnation in The New Testament (p. 36ff). God’s judgments at most lead to a temporary damnation, as they always have the purpose of correcting, disciplining and restoring the sinner. As other restorationists Cox believed that a judgment would take place in a future dispensation – in contrast to the preterist view popular amongst 19th century universalists (e.g. Hanson), who held that Jesus’ parables about judgment and the prophecies of Revelations were in most cases realized in the 1st century A.D.

An important, though not very developed, part of Cox’s discourse is his view of election (one might want to look for his posthumous The Hebrew Twins. A Vindication of God’s Ways with Jacob and Esau for more on this theme). Cox notes that when God elects and separates one person from the mass, it is always for the sake of others. No man, family, nation or church possesses any gift or privilege for its own use or welfare alone, says Cox (p. 159). That God is the savior of all human beings, especially those that believe (1 Tim 4,10), means that God saves all through the ministry of believers. The purpose of the Christian life is to serve or even die for others:

“My friends, if we love Christ, we need have no fear for our souls. In sundry places and in terms not to be mistaken, all who trust in Him are assured of an eternal salvation, a life that can never die. But if we truly love Him, we are willing even to die in order that the world may be saved: for did not He die to take away the sin of the world? and must not we be made partakers of his death, if we are to be glorified together with Him? Unless I can believe that God will deign to use me for the good of others, what is my life worth to me? Not to be capable of living and suffering for others, that is the true hell; but to be capable of, to be allowed to serve and suffer for others, is the true heaven: for this is the very life of God Himself, and of Christ Jesus his Son, and of the ever-blessed ever-quickening Spirit.” (Samuel Cox, Salvator Mundi, p. 143)

Central to Cox’s theory of salvation is his view of the atonement as the revelation of God’s love, rather than the condition for it: “Christ did not create, He only unveiled and disclosed, the self-sacrificing love of the Father.” Cox’s point is, that no person at any point in time is outside the redeeming love of God, as Christ’s sacrifice is an eternal reality.

“Although the Scriptures often speak of the sacrifice of Christ as both ordained and made from before the foundation of the world, and thus seek to lift it clean out of the limits of time, we commonly think of it only as a sacrifice made on a certain sacred day in our human calendar. And yet the Cross of Christ must speak to us of an eternal sacrifice, it must become the symbol of a divine and eternal passion, before we can rise to an adequate conception of its significance.” (Samuel Cox, Salvator Mundi, p. 166)