Guest post by Alexander Asciutto.

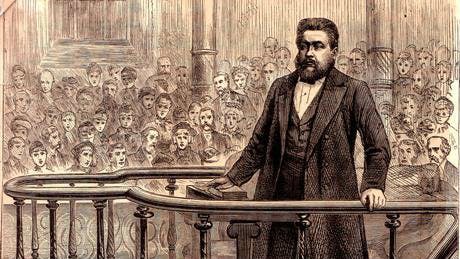

Charles Spurgeon, a renowned nineteenth-century Baptist preacher, delivered a sermon entitled, “Adoption,” at Exeter Hall–a hall on the north side of The Strand, London, England; in the sermon, he makes critical remarks regarding the doctrine of adoption and justification. [1] His remarks show that he believed that justification from eternity–the teaching that justification is an internal, immanent, and eternal act in God–to be a legitimate reformed position on the doctrine of justification. He states the following:

But there are one or two acts of God which, while they certainly are decreed as much as other things, yet they bear such a special relation to God’s predestination that it is rather difficult to say whether they were done in eternity or whether they were done in time. Election is one of those things which were done absolutely in eternity; all who were elect, were elect as much in eternity as they are in time. But you may say, Does the like affirmation apply to adoption or justification? My late eminent and now glorified predecessor, Dr. Gill, diligently studying these doctrines, said that adoption was the act of God in eternity, and that as all believers were elect in eternity, so beyond a doubt they were adopted in eternity. He further than that to include the doctrine of justification and he said that inasmuch as Jesus Christ was before all worlds justified by his Father, and accepted by him as our representative, therefore all the elect must have been justified in Christ from before all worlds.

As seen above, Spurgeon correctly understands election to be an act “done absolutely in eternity.” Amongst those of the reformed tradition, this is pretty much a given; there is not anyone, to my knowledge, who would be considered reformed were they to deny the eternal election of the believer. In arguing for election being from eternity, Spurgeon does not mention the distinction between immanent and transient acts of God, which would have been immensely helpful to his case.

As seen above, Spurgeon correctly understands election to be an act “done absolutely in eternity.” Amongst those of the reformed tradition, this is pretty much a given; there is not anyone, to my knowledge, who would be considered reformed were they to deny the eternal election of the believer. In arguing for election being from eternity, Spurgeon does not mention the distinction between immanent and transient acts of God, which would have been immensely helpful to his case.

Understanding the distinction between immanent and transient acts of God are critical in understanding the debate over the “timing” of justification. Immanent acts are internal to God whereas transient acts are external to God; those internal acts are eternal whereas the external are done in time. John Gill, whom Spurgeon calls his “predecessor,” comments on the eternal nature of acts that are immanent to God, writing, “They are eternal; as God himself is eternal, so are they; for, as some divines express it, God’s decrees are himself decreeing, and therefore if he is from everlasting to everlasting, they are so likewise.” [2]

To put it in the most succinct manner, immanent acts reside within the divine mind whereas transient acts find their existence in the temporal sphere. Were Spurgeon to have drawn this distinction, between immanent and transient acts, he might have concluded, with Gill, that “as God’s will to elect, is the election of his people, so his will to justify them, is the justification of them; as it is an immanent act in God, it is an act of his grace towards them, is wholly without them, entirely resides in the divine mind, and lies in his estimating, accounting, and constituting them righteous, through the righteousness of his Son; and, as such, did not first commence in time, but from eternity.” [3]

Spurgeon mentions one of Gill’s arguments: “inasmuch as Jesus Christ was before all worlds justified by his Father, and accepted by him as our representative, therefore all the elect must have been justified in Christ from before all worlds.” This is a conclusive argument, indeed; if Christ be eternally justified before the Father, and if we are represented in Christ from eternity, then we are viewed just as Christ was from eternity–eternally justified. This argument revolves around the eternal suretyship of Christ, whereby he resolved in eternity to be our representative and to take upon himself our case; and as the moment a man becomes the surety for a wrongdoer, the wrongdoer, on account of the surety, is free to go, even so, we are as free from the charge of sin from eternity as the spotless lamb of God. Surely, none would dispute that the sacrifice of Christ was determined, decreed, and resolved upon from eternity; nevertheless, in a section of Gospel Glory worth reading, Edward Drapes demonstrates the doctrine of the eternal suretyship of Christ to be a most scriptural one.

Spurgeon continues his remarks:

Now, I believe there is a great deal of truth in what he said, though there was a considerable outcry raised against him at the time he first uttered it. However, that being a high and mysterious point, we would have you accept the doctrine that all those who are saved at last were elect in eternity when the means as well the end were determined. With regard to adoption, I believe we were predestined hereunto in eternity, but I do think there are some points with regard to adoption which will not allow me to consider the act of adoption to have been completed in eternity. For instance, the positive translation of my soul from a state of nature into a state of grace is a part of adoption or at least it is an effect at it, and so close an effect that it really seems to be a part of adoption itself: I believe that this was designed, and in fact that it was virtually carried out in God’s everlasting covenant; but I think that it was that actually then brought to pass in all its fullness.

Spurgeon makes it clear that the sense in which these acts were “virtually carried out” from eternity is that the process of adoption and justification start in eternity, yet are not “completed in eternity.” In his view, justification is resolved upon from eternity, made possible by the cross of Christ, and actually brought into being the moment a man believes; in that he makes justification a process, he declares it to be transient, though he did not use the word, rather than an instantaneous, internal, immanent, and eternal act occurring in God. Spurgeon’s system, ultimately, fails.

If “it is God that justifieth,” Rom. 8:33, and if the act of justification lies solely in God “estimating, accounting, and constituting” sinners as righteous, then Spurgeon must be wrong in asserting that justification is a transient act, for these are all terms that denote an action of the divine mind, and consequently an action that is immanent and eternal. Justification, in its proper sense, is for God to consider Christ’s righteousness as ours, and as consideration is an act residing within the divine mind, it does not first have it’s being in time but from eternity, being an immanent and internal act of God. This is a sure, concise, and irrefutable principle on which the doctrine of justification from eternity rests; that it is the eternal God which justifieth.

Spurgeon continues:

So with regard to justification, I must hold, that in the moment when Jesus Christ paid my debts, my debts were cancelled — in the hour when he worked out for me a perfect righteousness it was imputed to me, and therefore I may as a believer say I was complete in Christ before I was born, accepted in Jesus, even as Levi was blessed in the loins of Abraham by Melchisedec; but I know likewise that justification is described in the Scriptures as passing upon me at the time I believe. “Being justified by faith,” I am told “I have peace with God, through Jesus Christ.” I think, therefore that adoption and justification, while they have a very great alliance with eternity, and were virtually done then, yet have both of them such a near relation to us in time, and such a bearing upon our own personal standing and character that they have also a part and parcel of themselves actually carried out and performed in time in the heart of every believer.

Spurgeon states about himself, “I was complete in Christ before I was born, accepted in Jesus, even as Levi was blessed in the loins of Abraham by Melchisedec.” Were he to stop at this statement, we would have much reason to rejoice, but Spurgeon negates these wonderful words within the next few sentences. He states that though he knows this to be true, he also knows the equally contradictory proposition, that he is only truly and actually justified upon believing, to be true; thus affirming some sort of irreconcilable paradox on the issue.

Lastly, Spurgeon states:

I may be wrong in this exposition; it requires much more time to study this subject than I have been able yet to give to it, seeing that my years are not yet many; I shall no doubt by degrees come to the knowledge more fully of such high and mysterious points of gospel doctrine. But nevertheless, while I find the majority of sound divines holding that the works of justification and adoption are due in our lives I see, on the other hand, in Scripture much to lead me to believe that both of them were done in eternity; and I think the fairest view of the case is, that while they were virtually done in eternity, yet both adoption and justification are actually passed upon us, in our proper persons, consciences, and experiences, in time, — so that both the Westminster confession and the idea of Dr. Gill can be proved to be Scriptural, and we may hold them both without any prejudice the one to the other.

Humbling himself, Spurgeon admits that his doctrine on the timing of justification very well may be wrong and that those like Gill, who spent much time “diligently studying these doctrines” could be correct. While he saw that many sound divines hold justification, in its proper sense, to be a transient act, such as sanctification and regeneration, he sees much in scripture that leads him “to believe that both of them were done in eternity,” such as election.

To conclude, it is necessary to address one of the weightier claims against the doctrine of justification from eternity brought forth by Spurgeon. As seen in the third block quote from Spurgeon, the doctrine of justification by faith is often asserted to contradict the doctrine of justification from eternity. I would argue, alongside many others, that “justification by faith is no more but the manifestation to us of what was really and actually done before; or a being persuaded more or less of Christ’s love to us; and that when persons do believe, that which was hid before doth then only appear to them.” [4] Understood in this light, the doctrine of justification by faith poses no threat to the notion of justification from eternity; yet, this is not the only solution. Nevertheless, there are numerous books in our possession from the seventeenth century and forward which are written, in part, to address this very objection that Spurgeon raises; in the future, these works will be published and expounded upon to further refute this objection.

Endnotes:

[1] The Complete Works of C. H. Spurgeon, Vol. 7: Sermon 360.

[2] John Gill, “Of the Internal Acts and Works of God; And of His Decrees in General.” In A Body of Doctrinal Divinity, II.I.

[3] John Gill, “Of Immanent and Transient acts of God, Particularly Adoption and Election.” In A Body of Doctrinal Divinity, II.V.

[4] In John Flavel’s A Blow at the Root of Antinomianism he argues that this idea is false–unsucessfully. It is uncertain whether he invented this statement which he was trying to refute, or if he quoted it from elsewhere.