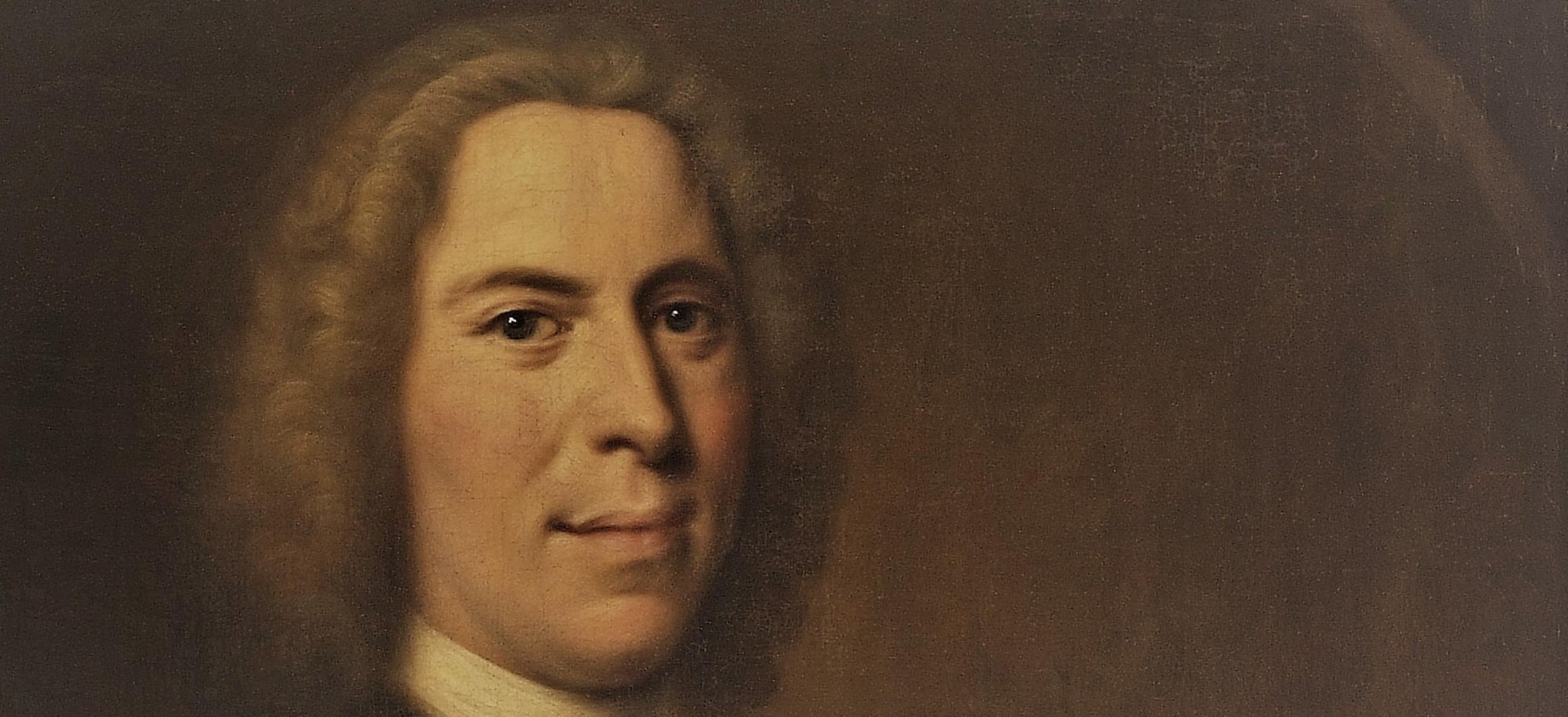

I’ve recently posted on Peter Böhler — the Moravian bishop whose missional zeal was an important inspiration for John Wesley, though they eventually splitted over Böhler’s allegedly universalistic tendencies. Reading the chapter on Continental Pietism in Robin Parry’s A Larger Hope?, I was surprised to learn that the more famous Nicolaus Zinzendorf (1700-1760), bishop of the Moravian Church, seems to have shared Böhler’s high eschatological hopes. Even if the evidence seems a bit thin, in the third discourse of Zinzendorf’s Sixteen Discourses on the Redemption of Man by the Death of Christ, Zinzendorf explicitly says that by the name of Jesus all “can and shall obtain life and salvation”:

“He must first manifest himself as Jesus every where, then the soul will also experience him as Christ. After the communication of grace in his blood, souls are also made partakers of his oil and anointing. The name of Jesus is his own proper name, which he bears as our flesh and blood for the benefit of all men, be they ever so dead sick, or ever so miserable and sinful, by this his name all can and shall obtain life and salvation.” (Zinzendorf, Sixteen Discourses on the Redemption of Man by the Death of Christ, III)

Notice that Zinzendorf is not just saying here, that all the faithful can and shall be saved, but that all men “can and shall”. This could at least be taken to mean, that he believed that all would eventually be saved. While Zinzendorf adds that “the name of Christ” only belongs to those that are his “redeemed one’s already”, the “already” may be read as keeping the possibility open, that all will eventually belong to Christ, i.e., that all for whom Jesus died will eventually be Christians. (Note: I haven’t been able to find the original German of Zinzendorf’s discourses, so the details of the language are somewhat uncertain).

Now, as a good pietist Zinzendorf was more concerned with true Christian discipleship and living than with dogma, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the rest of the discourse is mostly about what it means to call oneself a Christian. Nevertheless, the universalistic tone of Moravian theology and doctrine seems to have sparked some controversy. Parry mentions that Zinzendorf’s discourses were criticized by John Wesley, and that some controversy followed when Zinzendorf at a convocation in Pensylvania allegedly proposed an article saying that Jesus is “not only the Saviour of the faithful and the atonement for their sins, but also the atonement for the whole world and the Saviour of all men.” This statement is, of course, fully biblical (merging 1 Tim. 4:10 with 1 John 2:2).

The story of Moravians like Böhler and Zinzendorf should, as I’ve noticed before, remind us that holding high soteriological hopes for all humankind does not contradict the firm emphasis on mission and evangelism, for which the Moravians were known.