The following is a paper originally presented at a conference at International Baptist Theological Seminary (IBTS) in Amsterdam on how to reconcile conflicting convictions. The paper was also published in Baptistic Theologies (no. 1 Spring 2016).

A central discussion in Protestant orthodoxy has been that between those who affirmed the sovereignty and the predestining election of God on the one hand, and those who affirmed the general scope of the atonement and the freedom of human beings to reject grace on the other. While both assumed an eschatology where only some human beings would finally be saved, a third position was held by theologians who simultaneously affirmed the sovereignty of God and the generality of his love and the atoning sacrifice of Christ. Some of these were Anabaptists or Baptists, who argued that the conflicting opinions in Protestant orthodoxy about the sovereignty of God and the freedom of the human will could be reconciled by applying some sort of biblical universalism.

Introduction

Should we emphasize the sovereignty of God at the cost of having to narrow the scope of his love and mercy and the freedom of human beings? Or should we instead emphasize the universal scope of God’s love as well as the freedom of human beings to resist grace at the cost of God’s sovereignty? Questions such as these seem to have been at the core of many theological controversies in the slipstream of the Reformation.

The broad variety of answers makes the period of Protestant Orthodoxy somewhat confusing: Lutheran Orthodoxy seems to have had more in common with Erasmus, and later the Arminians, than with Luther, who in turn seems to have been more Calvinist than Calvin himself. The High and Hyper-Calvinists of the 18th century were neither Lutheran nor Calvinists in the sense of Calvin, while the Anabaptists and Baptists did not seem to embrace an idea of universal salvation as was claimed in the Augsburg Confession. Or did they? Well, some did, and some even saw the doctrine of universal salvation as a way of reconciling the conflicting beliefs about God’s omnipotence and sovereignty on the one hand and the freedom of the human will to resist the general grace of God on the other. This will be the topic of the following.

My first example is Hans Denck (1500-1527), a contemporary of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther, whose opposing views on the freedom of the human will Denck sought to reconcile by applying a concept of yieldedness or Gelassenheit. My second example is Georg Klein-Nikolai (1671-1723), author of The Everlasting Gospel, a work from around 1700 in which a form of restorationism is proposed as a way to reconcile Lutheran Orthodoxy with Reformed theology. My third and final example is the theology of Elhanan Winchester (1751-1797), who believed that a kind of biblical universalism much like that of The Everlasting Gospel could reconcile Calvinism and Arminianism especially as conceived by the Particular Baptists and the General Baptists respectively.

As already suggested in the above, the background of this whole discussion is the problem of how theology should handle the sovereignty and omnipotence of God on the one hand and the responsibility and freedom of human beings to choose between belief and unbelief on the other. This issue was at the core of one of the most important discussions of the Reformation, namely that between Erasmus of Rotterdam and Martin Luther. In 1524 Erasmus released his book On Free Will (De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio) in which he argued that human beings possess some degree of freedom in their relationship to God and that the traditional Augustinian doctrine of predestination was not biblical.

Luther, against Erasmus, famously held the view that the human will is not free in relation to God. As he put it, the human will is in bondage – either to God or the Devil. Thus it depends on the predestining decision of God alone whether a person will have saving faith in the Gospel or not. According to his revealed will it is true that God wants all people to be saved (1 Timotheus 2. 4), says Luther, but there is also a hidden will of God outside revelation that will not give all persons the capability of accepting faith.1 In other words, Erasmus defended the general scope of God’s love as well as the freedom of human beings to reject grace in spite of this love, while Luther held that God sovereignly and unconditionally decides who to love and who to hate – and who will as a result of this love have saving faith and who will not.

Yielding to God

With Erasmus many Anabaptists, such as Balthasar Hubmaier, held some notion of the freedom of the human will and the belief that human beings should actively choose to believe in or follow Christ.2 But this was just one of many doctrines which separated the Lutherans from the Anabaptists. Besides the obvious disagreement on baptism another important disagreement seems to lie behind the condemnations against the Anabaptists in the 17th article of the Augsburg Confession. This article condemns the Anabaptists for their alleged belief that there will be an end to the punishments of condemned men and devils.

The condemnations of the 17th article of the Augsburg Confession does not at face value reflect the conflicting opinions on the freedom of the human will. But even so, for those Anabaptists who were subject to the condemnations, there might have been an implicit connection between some sort of soteriological universalism and an alternative view on the freedom of the human will.

This was at least the case for the South German Anabaptist leader Hans Denck. Hans Denck was born in 1500, studied in Ingolstadt and became acquainted with the Anabaptists at the time of the Reformation.3 Hans Denck not only sought a middle way between Erasmus and Luther on the issue of the freedom of the will, but also argued that damnation is only a temporary step on the way to salvation. Damnation and salvation are not irreconcilable opposites but parts of a greater whole.

An important source of inspiration for Hans Denck seems to have been the anonymous work Deutsche Theologie, probably from the 14th century.4 In this work, which was also positively received by the young Martin Luther, a kind of spiritualism in the vein of German medieval mysticism is developed. An important element in the Deutsche Theologie is what has been called resignatio ad infernum. This theme is worked out as the human self is said to be unable of doing any good in and of itself. In order to be saved, the human self must be broken down in a spiritual hell where it is deprived of all hope, and as a result is made to turn to God. This framework was taken over by Hans Denck.

As was also common in the tradition of mysticism, Denck showed a high appreciation of paradoxes. According to Denck theological schisms and sects arise when people take out passages from Scripture and ignore the fact that there are always passages which seem to contradict each other. But truth can only be found, says Denck, by reconciling seemingly contradictory statements.5 Prophets can seem to disagree, but if they lead to God they all lead to truth.6 This approach to theological disagreements was also expressed in Denck’s positive approach to Jews and Judaism. Werner Packull has for this reason called Hans Denck ‘the ecumenical anabaptist’.7

Denck’s desire to reconcile oppositions can be seen clearly in his approach to the discussion on the freedom of the will. At face value there seems to be two possible options, namely that human beings are either free or unfree in their relation to God.8 But, says Denck, both claims are in themselves true. But when made by sinful human beings both claims are at the same time untrue, as they speak about human nature from human nature itself. But it makes no difference whether we call the human will free or in bondage. The truth about human freedom should be found in neither of these two claims, but in a third point. This third point is the breaking down of the human will, free or not, in yieldedness or Gelassenheit.

In his short treatise Divine Order, Denck describes how this works. Denck writes:

God desires everyone to be saved, 1 Timotheus 2. 4, 2 Peter 3, but knows full well that many condemn themselves, Romans 9. If then his will were to force anyone through a mere order, he could say the word this instant and it would happen, Matthew 8, Luke 7. But this would diminish his righteousness.9

So far, this sounds much like usual arguments for the freedom of human the will to choose between belief and unbelief. But Denck goes on to argue that as soon as the godless person rejects God he ‘has come to the place for which he was predestined, which is hell.’ But, says Denck:

He does not necessarily want to nor need he remain there, of course, Psalm 77; for even hell is open to the Lord and damnation has no cover, Job 26. [Hell] is not mightier than his strong arm except in the highest righteousness which we call his wrath, when he inflicts upon us the pains of hell, Psalm 18, and makes us aware of our misery that we might call on him in our despair for him to help us, Hosea 9.10

The point is that God inflicts on us the pains of hell in order to make us aware of our misery, so that we may eventually call upon God and be saved, Denck argues. Denck bases his position on passages in scripture such as Romans 11. 32 where Paul states that ‘God hath shut up all unto disobedience, that he might have mercy upon all‘ (ASV). God, in other words, humbles in order to save. But where this for Paul seems to have worked historically in the relationship between Israel and the Gentiles, for Denck it was more an inner, spiritual experience. Human beings need to go through an existential experience of being lost and damned in order to come to faith and thus salvation. Human beings are not saved from hell, but through hell.

In a similar way Denck in his confession states that the office of Christ is twofold (rather than threefold as, e.g., in Eusebius and Calvin) as Christ through Law and Gospel destroys the unbeliever and brings life to the believer. But, says Denck, ‘all believers were once unbelievers. Consequently, in becoming believers, they thus first had to die in order that they might thereafter no longer live for themselves, as unbelievers do, but for God through Christ […]’. David verifies this, Denck notes, as he says that ‘The Lord leads down into hell and up again’ (1 Samuel 2. 6-8).

While many scholars have held Denck to be a universalist others have argued that he was probably not since he did hold to a belief in some degree of human freedom to reject grace.11 I will not go further into this discussion here, but only mention that it is far from obvious that Denck believed that anyone would in fact keep on rejecting God forever. At any rate, the position of Hans Denck should not be considered a humanism of the Erasmian sort where human beings are not so depraved by nature that they are incapable of choosing their own destiny.12 By nature human beings are only free to do evil. But neither is Denck’s position that of Luther’s. Human beings are not forced into accepting grace, but as God works on the human will it will eventually break down and yield before God.

Hans Denck’s position could be characterized as a kind of critical spiritualism.13 Human beings cannot be said to be good by nature, as they are incapable of doing anything but evil by themselves, says Denck.14 In order to do good human beings must be led to faith by the spiritual crisis inflicted on the self by the judgment of God which breaks down the human self. This is why faith is not a matter of exercising the human will, free or not, but of not exercising the human will in Gelassenheit. In faith human beings become nothing to themselves and thus something to God.15 Human beings are not in this way predestined to belief or unbelief in the strict deterministic sense, but are made to yield by God’s active work in the spirit.

The Everlasting Gospel

While Luther’s view was taken over by Calvin and formulated in terms of a double predestination, a moderate version closer to Erasmus’ view was formulated by Melanchton as the claim that human beings, while not capable of choosing faith in God, are capable of resisting grace. This view became common in subsequent Lutheran Orthodoxy as we know it from the Formula of Concord in which it is repeatedly stated that human beings are capable of resisting the Holy Spirit.16

Thus in the 17th century the positions held by Luther and Erasmus were now more or less represented by Calvinism and Lutheran Orthodoxy respectively. While the Reformed (Calvinist) side on the one hand accentuated double predestination and the belief that God sovereignly saves the elect, Lutheran Orthodoxy emphasized the generality of the atonement and the ability of human beings to resist grace on the other.

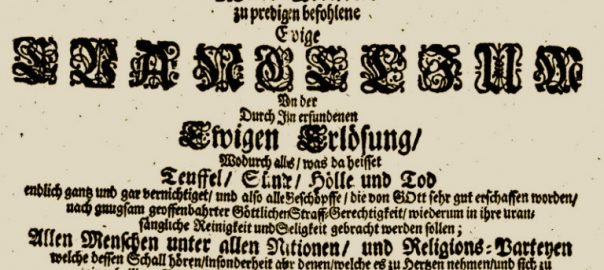

Now, a theological strategy somewhat similar to that of Denck’s can be found in Georg Klein-Nikolai’s pseudonymous work Das von Jesu Christo dem Richter der Lebendigen und der Todten, aller Creatur zu predigen befohlene ewige Evangelium, von der durch Ihn erfundenen ewigen Erlösung, wodurch alles dem Richter der Lebendigen und der Todten, aller Creatur zu predigen befohlene ewige Evangelium, von der durch Ihn erfundenen ewigen Erlösung, wodurch alles published in the name Paul Siegvolck.

Georg Klein-Nikolai was an associate of the radical pietist Johann Wilhelm Petersen and his theology seems to have drawn on Petersen, who was in turn influenced by Jane Leade and the Philadelphians. Another source of influence may have been the Schwarzenau Brethren, a radical pietistic group of German Baptists also known as the Neue Täufer or the Tunkers.17 Alexander Mack, the founder of the Schwarzenau Brethren, expressed a belief that after the collapse of several eternities or aeons there would be a final and universal restoration of all things, in which the godless through Christ would finally be saved from their torments in hell.18 It is not, however, necessary to talk or speculate much about it, says Mack. It is much better to practice truth here and now than deliberating about how to escape the torments of hell at a later point. Even though the doctrine of the universal restoration of all things is true, ‘it should not be preached as a gospel to the godless’.

The doctrines of radical pietist universalists such as Mack and Petersen seem to have been derived partly from Jacob Boehme and perhaps Origen. The theology of The Everlasting Gospel was similarly Origenistic in its understanding of the history of salvation as progressing through ages or aeons, culminating in a final telos, the restitution of all things or apokatastasis panton through Christ. But while Origen eagerly emphasized human freedom, The Everlasting Gospel is more reserved.

It does seem, however, that the author of The Everlasting Gospel allows some degree of free choice of human beings between belief and unbelief. Those who chooses not to believe will be subject to harsh punishments in this and the coming world. But this is not an eschatological freedom in the sense that human beings in particular points of time can ultimately choose their final destination. God has designed punishments in order to correct the sinner so that the sinner will eventually be led into salvation – again, in this world or the world to come. Klein-Nikolai writes:

The Holy Scripture declares that wicked men both can and do oppose and resist God; As also that no creature can resist the will of God. Though here seems an apparent contradiction, yet both these positions may well consist together;19

The creatures may resist the will of God, says Klein-Nikolai. This does not mean, however, that there is an ability and power in them, whereby they might repel and conquer the power and might of God that works in and upon them, in such a way that God could never get his will with the rebellious creatures.

The belief that creatures are in all eternity capable of resisting God makes creatures stronger than God and thus opens the way to all kinds of ‘iniquity and atheistic mockery’, says Klein-Nikolai.20 It is only with God’s permission that the creature is allowed to resist God. The purpose is, says Klein-Nikolai, that ‘the creatures, who will not voluntarily choose the salvation and well-being offered to them, may taste of the bitter fruits of their disobedience’. As a result the rebellious creatures will be finally conquered and thus ‘give themselves up to their Creator’, who is ‘able to subdue all’.21

The point is again, as with Hans Denck, that even if human beings have some degree of freedom, this freedom is essentially relative and subordinated to God’s sovereignty. Human beings do not have the ultimate freedom to choose their own destiny. God’s purposes cannot be thwarted. But in distinction to the more Augustinian view of the human will as conceived by High Calvinism, God does not work directly upon the will or mind of human beings but only indirectly. By inflicting suffering on the human person God directs the will of that person into eventually accepting his free grace.

As with Denck it is central for Klein-Nikolai that it is simultaneously true that human beings are capable of resisting God on the one hand and that no creature can resist the will of God on the other. But truths most be reconciled in God’s plan of salvation. And moreover, Klein-Nikolai likewise saw the doctrine of universal salvation as having a reconciliatory potential between conflicting opinions on the freedom of the human will. As he says:

This holy doctrine likewise shows the right foundation of divine election and eternal reprobation, and demonstrates both to Lutherans and Calvinists as well wherein each party is right, as what they want of the understanding of this important point.22

Lutheran Orthodoxy is correct in claiming that God wills the salvation of all human beings and that he saves all who in this life come to faith in Christ. Likewise the Calvinists are right in teaching that all who God wills to be saved shall actually be saved: ‘Those whom God will have to be saved, will actually be saved. Now God plainly declares in his word, that he will have all men to be saved; therefore all men will be really saved at last.’23 Klein-Nikolai adds that the doctrine of universal restoration is also capable of deciding the dispute with the Roman Catholics about purgatory.24

The Everlasting Gospel was made available for the American audience by the German Baptists (Schwarzenau Brethren) of Germantown in Pennsylvania as it was translated and published in English in 1753. It was this book which would become a main source of inspiration for Elhanan Winchester, who will be discussed in the following.

The Outcasts Comforted

Elhanan Winchester was born in Massachusetts, USA, in 1751. He was raised in a Congrationalist setting but after a conversion experience he joined a Free Will (General) Baptist church in which he became a preacher. Winchester seems to gradually have become convinced of a High Calvinist theology in the vein of John Gill, and, after renouncing Arminianism, Winchester became a minister in a Calvinistic (Particular) Baptist church, first in Bellingham (MA) and then in Welsh Neck (SC).

Winchester originally came from a moderate Calvinist standpoint and only subsequently became convinced of the High Calvinism of John Gill, who believed that the Gospel should be preached primarily, or only, to the elect rather than everyone indiscriminately. As suggested by Finn it was his missionary zeal and the possibility to preach repentance and conversion to all human beings that later made Winchester drop High Calvinism. Winchester himself writes that he esteemed John Gill almost as an oracle, but at some point began to adopt a more open and general method of preaching as he found himself stirred up to exhort his fellow creatures to repent and believe the Gospel. Winchester points out, however, that he did not consider whether this was consistent with strict Calvinism or not.25

After a friend of Winchester’s in 1778 brought the English edition of The Everlasting Gospel to Welsh Neck, Winchester became more and more convinced of universalism. Later Winchester would make contact to the German Baptists of Germantown and he would write the foreword for a later edition of The Everlasting Gospel which he published in London in 1792. In the foreword to this edition Winchester noticed that:

The system held out in the following pages appears to me the only one that in the least bids fair to unite the two great bodies of Christians, that have so long and so bitterly opposed each other, viz. those who assert that Christ died for all, and yet that there shall be but few, comparatively, that shall finally derive any saving benefit therefrom; and those who assert that all for whom the savior died shall indeed be saved, but that he died only for a few.26

Winchester notes that it seems highly unlikely that either of these sects should change their principles. The one charges the other with a lack of benevolence while the other charges the one with lacking a proper view on the omnipotence of God. For a reconciliation to take place between these two opinions, it must be ‘on some middle ground where both may meet without giving up their favorite opinions’, says Winchester.27 Such a middle ground is exactly what ‘the system of the Universal Restoration’ offers. As soon as the doctrines of Universal Restoration are accepted, says Winchester, it will bring reconciliation between the two opposing bodies of doctrines in Christian theology.

In Elhanan Winchester’s time and context the conflicting convictions fleshed out in the above were represented by Arminianism and Calvinism. In Reformed theology the opposition between an idea of some degree of freedom of the will to choose faith in the Gospel, and the idea that there is no such freedom, had become most explicit during the controversies on the views of Jacob Arminius (1560-1609) and the Remonstrants who shared his views on conditional election (the condition being foreseen faith) and the general scope of the atonement.

The main points of Arminianism, though maybe not exactly expressive of the views of Jacob Arminius himself, is often formulated something along the following lines: (1) In spite of sin, human beings have the freedom to choose between belief and unbelief, (2) human beings are never so controlled by God that they cannot reject the Gospel, (3) God’s election of the saved is prompted by His foreseeing that they will believe of their own accord, (4) Christ’s death did not ensure the salvation or the gift of faith to anyone, but created a possibility of salvation for all who believe, and (5) it rests with believers to keep themselves in a state of grace by keeping up their faith.

In response to Arminianism a synod was held in Dordrecht (the English name being Dort) in 1618-1619 by the Dutch Reformed Church together with eight voting representatives from foreign Reformed churches. Against the Arminians the Synod of Dort formulated five points which would become known in the English by the T.U.L.I.P. acronym. The acronym is perhaps most famous for its insistence on the unconditionality of election and the irresistibility of grace coupled with its claim that the atonement was limited to the elect.

In the 17th century this debate became relevant for Baptists who formed separate denominations. On the one hand there were the General Baptists who followed the first English Baptists John Smyth’s and Thomas Helwys’ beliefs (similar to the Mennonites) in a general atonement combined with a belief in the freedom of the human will to accept the Gospel and follow Christ. On the other hand there were the Particular Baptists who followed the Synod of Dort in holding to a limited atonement combined with a belief in irresistible grace.28

It was these positions that Winchester sought to reconcile using the universalist doctrines contained in The Everlasting Gospel. For Winchester, universalism offered a way of affirming the key principles of both High Calvinism and Arminianism in ‘one grand system of benevolence’, as he puts it in his dialogues on Universal Restoration.29 This is not to say that Winchester necessarily had a very high view of theological systems. In his dialogues on universal restoration he even suggests that it is exactly because people have preferred systems to the simple truth of the gospel that they have thought it necessary to diminish the omnipotence or love of God: ‘O the mischiefs of bigotry, prejudice, and vain attachment to system!’30.

Even so, in On the Outcasts Comforted it is as a system of thought that universal restoration is thought to reconcile the conflicting bodies of theological doctrine. What Winchester proposes is an ecumenical system of thought. As Robin Parry notes, ‘the universalist system understood as a theological via media seemed to Winchester, perhaps somewhat naïvely, to have some ecumenical potential in bringing Calvinists and Arminians together.‘31 That Winchester’s ecumenical hopes were really quite naïve is clear from the controversy that his views awoke.

Of course Winchester’s universalism was by many not seen as being very conciliatory – on the contrary. Winchester’s successor in Welsh Neck saw Winchester as ‘the means of dividing the Baptist Church‘ in the city, while Winchester himself relates how he was treated with enmity from former friends.32 In the following years after Winchester’s profession of universalism he and his congregation would experience exclusion and marginalization from the broader evangelical community which would eventually lead to the foundation of an independent Universal Baptist church.

In 1782 Winchester addressed this issue in a sermon delivered at the University in Philadelphia. The sermon was later printed with the title The Outcasts Comforted: A SERMON Delivered at the University in Philadelphia, January 4, 1782 To the Members of the BAPTIST CHURCH, who have been rejected by their Brethren, For holding the Doctrine of the final Restoration of all Things. Winchester argues in the sermon that it is strange that the Universal Baptists are looked upon as heretics when they only affirm the doctrines already held by others:

I have often considered it with astonishment, that two ministers shall preach, and prove what they say from the scriptures, and neither of them shall be looked upon as holding damnable heresy, and yet we shall be looked upon as the worst of heretics by both of them, and all their people, for believing only what both of them put together have asserted.33

Winchester’s attempt to reconcile Arminianism and Calvinism should not be confused with the so-called Middle-Way Calvinism which sought to avoid the doctrinal conflicts between the two, often simply by not mentioning the extreme positions. Rather, Winchester’s position takes in the extremes in a very explicit way and makes them part of a greater system. With Arminianism Winchester affirms that God loves all, while with Calvinism Winchester affirms that all the object’s of God’s love will be saved. And with Arminianism Winchester affirms that God desires all people to be saved, while with Calvinism he affirms that all God’s purposes will be fulfilled. With Arminianism Winchester affirms that Christ died for all, and with Calvinism he affirms that all for whom Christ died will be saved so that the blood of Christ was not shed in vain: ‘One will declare that the blood of Jesus Christ was freely shed for all; the other, that his blood is infinitely sufficient to cleanse and purify all. This is what we believe.’34

So how should we characterize Winchester’s position? Based on Winchester’s own claims Robin Parry suggests that Winchester believed in a general atonement and universal salvation from early on, but suppressed these beliefs in order to ‘conform to the Calvinist theology he had been raised with’.35 This does not, however, match well with Winchester’s other claims of having esteemed John Gill ‘almost as an oracle’, made in the foreword to the dialogues, and the fact that he joined the Calvinist Baptist church in Bellingham (MA).36 According to Finn, Winchester believed in High Calvinism for a period, but ‘did not reject Calvinism for universalism, but rather rejected High Calvinism for Arminianism, though his commitment to universal penal substitutionary atonement encouraged him to eventually affirm universal salvation.’37 Winchester only left the ‘revival-friendly Baptist evangelicalism of his early ministry’ for a similarly revival-friendly conversionistic or eschatologically conscious evangelical universalism.38

But was Winchester an Arminian more than a Calvinist as the above suggests? Hardly. Winchester describes the revelation of Christ’s love that converted him as compelling (‘a manner as constrained me’), so it seems that we are not here dealing with the Arminian freedom to choose between belief and unbelief.39 The counsel of God shall stand and he will perform his pleasure, notwithstanding all the opposition that men can make, says Winchester with reference to Isaiah (Isaiah 46. 10). If God will have all men to be saved, as we hear in the first epistle to Timothy (1 Timotheus 2. 4) and if God is determined to perform his pleasure and if nothing is impossible with God, as stated in Luke 1. 37, then ‘is not the doctrine of the Restoration true?’, Winchester asks rhetorically.40

God gets his will by inflicting pain on the human self in order to make it yield. In this way Winchester, as Denck and Klein-Nikolai, affirms that God only punishes in order to correct: ‘Punishment to a certain degree, inflames and enrages, in a most amazing manner; but continued longer, and heavier, produces a contrary effect–softens humbles, and subdues.’41 But God is love from the beginning, and his love towards human beings does not only begin in the moment that persons are converted. It seems that for Winchester, when the love of God is revealed to a person it does not begin at that point but is simply made manifest.42 This looks like the idea of eternal justification (not to be confused with supralapsarianism, though apparently compatible with this idea) which can be found in High Calvinism where the sinner is not redeemed in the moment of faith but from eternity, so that the moment of faith is only the point in time where the sinner realizes that he or she is already justified and redeemed from before creation.

It does not seem that Winchester dropped Calvinism for Arminianism, or that he was never really a Calvinist, but rather that he found a way to combine what he saw as the core principles of both. Winchester took in and kept Calvinism’s belief in the sufficiency of the cross to redeem sinners and that God in his sovereignty will in the end get his will and save all the objects of his love. It was only the soteriological particularism of Calvinism that Winchester left behind as he embraced universalism and an Arminian method of preaching.

The more precise way of characterizing Winchester’s position would be that he was both a Calvinist and an Arminian, in so far as he simultaneously emphasized the sovereignty and omnipotence of God on the one hand and the love of God and the generality of the atonement on the other. In this he was not far from Hans Denck and Georg Klein-Nikolai.

Conclusion

The views described above were not new. Gregory of Nyssa argued in the 4th century that the perfections of God implies all His other perfections, since the opposite of one perfection can never be reconciled with other perfections.43 For Gregory this meant that God’s goodness and his righteousness are never exclusive but rather two sides of the same coin – and that all would eventually because of this be saved, not from but through death. It was this kind of theology which can be recognized later in, e.g., the anonymous Deutsche Theologie – the 14th century anonymous work that influenced Hans Denck so much, and which seems to have had a greater impact on Protestant theology than has often been acknowledged.

The ecumenical potential in reconciling conflicting positions on the omnipotence and love of God and the freedom of human beings was noticed by theologians of different streams in the 19th and 20th centuries. But in a Protestant context this tradition of thinking to a large degree originated in a (b)aptist setting. The future will show if baptists are capable of learning from this aspect of their tradition. This is not to say that all baptists should suddenly turn soteriological universalists (something which is unlikely to happen, though miracles do occur, also among baptists), but rather that we can learn from the theological method of bringing together opposites in a larger whole as a way of reconciling conflicting convictions.

This is not to say that we should at all costs construct complex theological systems, but rather that we may also have to learn to keep apparent as well as very real contradictions, paradoxes and conflicts alive without ultimately choosing the one pole over the other. That many modern protestants have become better at at least respecting differences among themselves seem to be clear, but respect for differing opinions must not be confused with post-modern relativism or subjectivism, but can just as well be seen as a particular theological method which can be found in the larger baptist tradition.

As Robin Parry remarks, one of the truly inspiring things about Winchester was his belief that Christians must debate with love and gentleness, and with an openness to being persuaded to change their views in the light of Scripture.44 While Klein-Nikolai may have been more stern in his views, he too held an ecumenical hope. A similar hope seems to have been held by Hans Denck who may have been even more cautious than Winchester in his attempts to avoid controversy and reconcile conflicting opinions. At the end of the day, what they all teach us is that insisting on God’s love and sovereignty is not a bad way of overcoming doctrinal disputes, no matter what positions we may hold.

Bibliography

Hans Denck, Schriften. T. 1-3, Quellen und Forschungen zur Reformationsgeschichte / Bd. 24.6. (ed. Walter Fellman, 1956)

Nathan A. Finn, ‘The Making of a Baptist Universalist: The Curious Case of Elhanan Winchester’, Paper Presented to the Baptist Studies Group Evangelical Theological Society San Francisco, California November 16, 2011 <https://www.academia.edu/4404295/The_Making_of_a_Baptist_Universalist_The_Curious_Case_of_Elhanan_Winchester> [accessed 24 November 2015]

Rufus M. Jones, Spiritual Reformers in the 16th and 17th Centuries (London: Macmillan & Co., 1914)

Georg Klein-Nikolai, The Everlasting Gospel (Copenhagen: Apophasis, 2015) <http://www.apophasis.dk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/The-Everlasting-Gospel.pdf>

Morwenna Ludlow, ‘Why Was Hans Denck Thought To Be a Universalist?’, in The Journal of Ecclesiastical History Issue 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 257-274.

Martin Luther (ed.), Eyn Deutsch Theologia, etc. (Wittenberg 1518)

Alexander Mack, Rights and Ordinances; trans. H. R. Holsinger, History of the Tunkers and the Brethren Church (Oakland, Cal.: Pacific Press Publishing Co., 1901).

Kirk R. MacGregor, ‘Hubmaier’s Concord of Predestination with Free Will’, in Direction: A Mennonite Brethren Forum 35, no. 2 (2006), pp. 279-99.

Werner O. Packull, Mysticism and the Early South German-Austrian Anabaptist Movement 1525-1531 (Pennsylvania: Herald Press, 1977).

Robin A. Parry, ‘The Baptist Universalist: Elhanan Winchester (1751-97)’ <https://www.academia.edu/8643336/_The_Baptist_Universalist_Elhanan_Winchester_1751_97_> [accessed 24 November 2015]

Johannes Aakjær Steenbuch, ‘Kærlighedens dialektiker: Karakteristik af Hans Dencks kritiske spiritualisme’, in Dansk Teologisk Tidsskrift 77/3 (Copenhagen: Anis, 2014), pp. 218-234.

Peter Toon, The Emergence of Hyper-Calvinism in English Nonconformity,1689-1765 (London: The Olive Tree, 1967).

Elhanan Winchester, The Universal Restoration: exhibited in a series of dialogues between a minister and his friend: comprehending the substance of several conversations that the author hath had with various persons, both in America and Europe, on that interesting subject, wherein the most formidable objections are stated and fully answered (UR) (London: Gillet, 1788).

Elhanan Winchester, The Outcasts Comforted. A sermon delivered at the University of Philadelphia, January 4, 1782 (Philadelphia: Towne, 1782).

Elhanan Winchester, Letter to the Rev. C. E. De Coetlogon, A.M. Editor of President Edwards’s lately revised sermon on the eternity of Hell-torments (London: Scollick, 1789).

1E.g., Martin Luther, De Servo Arbitrio (1525), WA 18,685.

2Kirk R. MacGregor, ‘Hubmaier’s Concord of Predestination with Free Will’, in Direction: A Mennonite Brethren Forum 35, no. 2 (2006), pp. 279-99; Morwenna Ludlow, ‘Why Was Hans Denck Thought To Be a Universalist?’, in The Journal of Ecclesiastical History Issue 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 257-274.

3See Clarence Bauman, The Spiritual Legacy of Hans Denck (Leiden: Brill, 1991).

4Eyn Deutsch Theologia, etc. (Wittenberg 1518); Bernard McGinn, The Harvest of Mysticism (New York: The Crossroad Pub. Co., 2005), p. 393.

5Hans Denck, Schriften. T. 1-3, Quellen und Forschungen zur Reformationsgeschichte / Bd. 24.6. (ed. Walter Fellman) (Gütersloh, 1956); Denck II.68.14; Denck II.58.18-21.

6Denck II.65.33.

7Werner O. Packull, Mysticism and the Early South German-Austrian Anabaptist Movement 1525-1531 (Pennsylvania: Herald Press, 1977).

8Denck II.107.24-25.

9Denck II.90.23-26.

10Denck II.92.10-17.

11Ludlow 2004, pp. 257-274.

12In this I tend to disagree with, e.g., Rufus Jones, Werner Packull and others. See Rufus M. Jones, Spiritual Reformers in the 16th and 17th Centuries (London: Macmillan & Co., 1914); Packull 1977, p. 58.

13See Johannes Aakjær Steenbuch, ‘Kærlighedens dialektiker: Karakteristik af Hans Dencks kritiske spiritualisme’, in Dansk Teologisk Tidsskrift 77/3 (Copenhagen: Anis, 2014).

14Denck II.54.1-10.

15Denck II.33.15-24. Baptism, by the way, should follow this inner experience as an outward sign of an already present inner reality, says Denck.

16E.g. Formula of Concord, XI. 39; 41; 73; 78.

17It is not clear how closely associated Klein-Nikolai was with the Schwarzenau Brethren, or whether he was one of them, but his theology seems to express some basic ideas of theirs.

18Alexander Mack, Rights and Ordinances; trans. H. R. Holsinger, History of the Tunkers and the Brethren Church (Oakland, Cal.: Pacific Press Publishing Co., 1901), pp. 113-115.

19Georg Klein-Nikolai, The Everlasting Gospel (Copenhagen: Apophasis, 2015 (1700)), p. 18

20Klein-Nikolai, p. 19

21Klein-Nikolai, pp. 16-17

22Klein-Nikolai, p. 176

23Klein-Nikolai, p. 177

24Klein-Nikolai, pp. 176-178.

25Winchester, The Universal Restoration, pp. viii-ix.

26Winchester 1792, foreword to The Everlasting Gospel.

27Winchester 1792, foreword to The Everlasting Gospel.

28A leading proponent of Particular Baptist theology was the English Baptist pastor and biblical scholar John Gill (1697-1771) whose views are sometimes described as Hyper-Calvinism. Peter Toon, The Emergence of Hyper-Calvinism in English Nonconformity, 1689-1765 (London: The Olive Tree, 1967).

29Winchester, The Universal Restoration II.A3 (chapter II, answer 3).

30Winchester, The Universal Restoration III.A10.

31Parry 2011, p. 31.

32Church records of Welsh Neck, Pee Dee, Sept. 5; Winchester, The Universal Restoration, p. xvii.

33Winchester 1782, The Outcasts Comforted.

34Winchester 1782, The Outcasts Comforted.

35Parry 2011, p. 3.

36Winchester, The Universal Restoration, pp. viii-ix.

37Nathan A. Finn, ”The Making of a Baptist Universalist”, p. 12.

38Nathan A. Finn, ”The Making of a Baptist Universalist”, p. 15. Finn distinguishes this form of universalism from the non-conversionistic universalism of John Murray and others who believed that the general atonement of Christ was sufficient for saving all without conversion in this life.

39Winchester, The Universal Restoration III.A2.

40Winchester, The Universal Restoration III.A5.

41Winchester, The Universal Restoration IV.A22.

42Winchester, The Universal Restoration III.Q9 (chapter 3, question 9).

43Gregory of Nyssa, Orationes viii de beatitudinibus IV, GNO 118-119.

44Robin Parry 2011, p. 35.