From J.W. Hanson’s Bible Threatenings Explained.

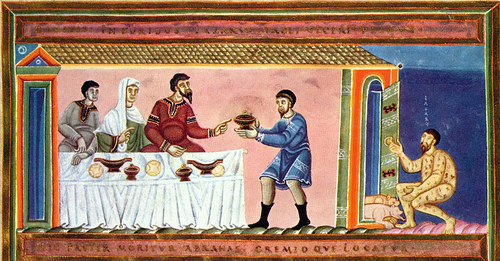

“And it came to pass, that the beggar died, and was carried by the angels into Abraham’s bosom; the rich man also died, and was buried; and in Hell (Hades) he lifted up his eyes, being in torment, and seeth Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom.” (Luke 14:22-23)

If this is a literal history, as is sometimes claimed, of the after-death experiences of two persons, then the good are carried about in Abraham’s bosom; and the wicked are actually roasted in fire, and cry for water to cool their parched tongues. If these are figurative, then Abraham, Lazarus, Dives and the gulf, and every part of the account, are features of a picture, an allegory, as much as the fire and Abraham’s bosom. If it be history, then the good are obliged to hear the appeals of the damned for that help which they cannot bestow! They are so near together as to be able to converse across the gulf, not wide but deep. It was this opinion that caused Jonathan Edwards to teach that the sight of the agonies of the damned enhances the joys of the blest!

The story is not fact, but a parable.

This is denied by some Christians, who ask, does not our Savior say: “There was a certain rich man?” etc. True, but all his parables begin in the same way, “A certain rich man had two sons,” and the like. In Judges 9, we read: “The trees went forth, on a time, to anoint a king over them, and they said to the olive tree, reign thou over us.” This language is positive, and yet it describes something that never could have occurred. All fables, parables, and other fictitious accounts which are related to illustrate important truths have this positive form, to give force, point, life-likeness to the lessons they inculcate.

Dr. Whitby says: “That this is only a parable and not a real history of what was actually done, is evident from the circumstances of it, namely, the rich man lifting up his eyes in Hell, and seeing Lazarus in Abraham’s bosom, his discourse with Abraham, his complaint of being tormented in flames, and his desire that Lazarus might be sent to cool his tongue, and if all this be confessedly parable, why should the rest be accounted history?”

Lightfoot and Hammond make the same general comments, and Wakefield remarks, “To them who regard the narrative a reality it must stand as an unanswerable argument for the purgatory of the papists.”

We give an indubitable proof that this is a parable. The Jews have a book, written during the Babylonish Captivity, entitled Gemara Babylonicum, containing doctrines entertained by Pagans concerning the future state, not recognized by the followers of Moses. This story is founded on heathen views. They were not obtained from the Bible, for the Old Testament contains nothing resembling them. They were among those traditions which our Savior condemned when he told the Scribes and Pharisees, “Ye make the word of God of none effect through your traditions,” and when he said to his disciples, “Beware of the leaven, or doctrine, of the Pharisees.”

Our Savior seized the imagery of this story, not to endorse its truth, but just as we now relate any other fable. He related it as found in the Gemara, not for the story’s sake, but to convey a moral to his hearers; and the Scribes and Pharisees to whom he addressed this and the five preceding stories, felt–as we shall see–the force of its application to them.

Says Dr. Geo. Campbell: “The Jews did not, indeed, adopt the pagan fables on this subject, nor did they express themselves entirely, in the same manner; but the general grain of thinking, in both, came pretty much to coincide. The Greek Hades they found well adapted to express the Hebrew Sheol. This they came to conceive as including different sorts of habitations, for ghosts of different characters.”

Now as nothing resembling these ideas is found in the Old Testament, where did the Jews obtain it, if not from Greek mythology?

The commentator, Macknight (Scotch Presbyterian) says truly: “It must be acknowledged that our Lord’s descriptions are not drawn from the writings of the Old Testament, but have a remarkable affinity to the descriptions which the Grecian poets have given. They represent the abodes of the blest as lying contiguous to the region of the damned, and separated only by a great impassable gulf in such sort that the ghosts could talk to one another from the opposite banks. If from these resemblances it is thought the parable is formed on the Grecian mythology, it will not at all follow that our Lord approved of what the common people thought or spoke concerning these matters, agreeably to the notions of Greeks. In parables, provided the doctrines inculcated are strictly true, the terms in which they are inculcated may be such as are most familiar to the people, and the images made use of are such as they are best acquainted with.”

But if it were a literal history, nothing could be gained for the terrible doctrine of endless torment.

It would oblige us to believe in literal fire after death, but there is not a word to show that such fire would never go out. We have heard it claimed that the punishment of the rich man must be endless, because there was a gulf fixed so that those who desired to, could not cross it. But were this a literal account, it would not follow that the gulf would last alway. For are we not assured that the time is coming when “every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low?” Isa. 40:4. When every valley is exalted, what becomes of the great gulf? And then there is not a word said of the duration of the sufferings of the rich man. If the account be a history is must not militate against the promise of “The restitution of all things spoken by the mouth of all God’s holy prophets since the world began.” There is not a word intimating that the rich man’s torment was never to cease. So the doctrine of endless misery is, after all, not in the least taught here. The most that can be claimed is that the consequences of sin extend into the future life, and this is a doctrine that we believe just as strongly as can any one, though we do not believe they will be endless, nor do we believe that the doctrine is taught in this parable, nor in the Bible use of the word Hell.

Charles Kingsley, the celebrated English author, says in his “Letters”: “You may quote the parable of Dives and Lazarus (which was the emancipation from the Tartarus theory) as the one instance in which our Lord professedly opens the secrets of the next world, that he there represents Dives as still Abraham’s child, under no despair, not cut off from Abraham’s sympathy, and under a direct moral training of which you see the fruit. He is gradually weaned from the selfish desire of indulgence for himself, to love and care for his brethren, a divine step forward in his life, which of itself proves him not to be lost. The impossibility of Lazarus getting to him, or vice versa, expresses plainly the great truth that each being is where he ought to be at that time, interchange of place, (i.e., of spiritual state) is impossible. But it says nothing against Dives rising out of his torment, when he has learnt the lesson of it, and going where he ought to go.”

So that on the theory that this is a literal account, it affords no evidence of endless torment.

But allowing for a moment that this is intended to represent a scene in the spirit world, what a representation we have! Dives is dwelling in a world of fire in the company of lost spirits, hardened by the depravity that must possess the residents of that world, and yet, yearning with compassion for those on earth. Not totally depraved, not harboring evil thoughts, but benevolent, humane. Instead of being loyal to the wicked world in which he dwells, as any one bad enough to go there should be, he actually tries to prevent migration thither from earth, while Lazarus is entirely indifferent to everybody but himself. Dives seems to have more mercy and compassion than does Lazarus.

But what does the parable teach?

That the Jewish nation, and especially the Scribes and Pharisees were about to die as a power, as a church, as a controlling influence in the world; while the common people among them, and the Gentiles outside of them, were to be exalted in the new order of things. The details of the parable show this: “There was a certain rich man clothed in purple and fine linen.” In these first words, by describing their very costume, the Savior fixed the attention of his hearers on the Jewish priesthood. They were, emphatically, the rich men of that nation. His description of the beggar was equally graphic. He lay at the gate of the rich, only asking to be fed with the crumbs that fell from the table. Thus dependent were the common people, and the Gentiles, on the scribes and Pharisees. We remember how Christ once rebuked them for shutting up the kingdom of heaven against these. They lay at the gates of the Jewish hierarchy, for the Gentiles were literally restricted to the outer court of the temple. Hence in Rev. 11:12, we read; “But the court, which is without the temple, leave out, and measure it not, for it is given unto the Gentiles.” They could only walk the outer court, or lie at the gate. The brief, graphic descriptions given by our Savior, at once showed his hearers that he was describing those two classes, the Jewish priesthood and nation, on the one hand, and the common people, Jews and Gentiles, on the other.

The rich man died and was buried. This class died officially, nationally, and its power departed. The kingdom of God was taken from them, and conferred on others. The beggar died. The Gentiles, publicans and sinners, were translated into the kingdom of God’s dear son, where is neither Jew nor Greek, but where all are one in Christ Jesus. This is the meaning of “Abraham’s bosom.” They accepted the true faith and so became one with faithful Abraham. Abraham is called the father of the faithful, and the beggar is represented to have gone to Abraham’s bosom, to denote the fact, which is now history, that the common people and Gentiles accepted Christianity and have since continued Christian nations, enjoying the blessings of the Christian faith.

What is meant by the torment of the rich man?

The misery of those proud men, when, soon after, their land was captured, and their city and temple possessed by barbarians, and they scattered like chaff before the wind–a condition in which they have continued from that day to this. All efforts to bless them with Christianity have proved unavailing. At this very moment there is a great gulf fixed so that there is no passing to and fro. And observe, the Jews do not desire the gospel. Nor did the rich man ask to enter Abraham’s bosom with Lazarus. He only wished Lazarus to alleviate his sufferings by dipping his finger in water and cooling his tongue. It is so with the Jews today. They do not desire the gospel; they only ask those among whom they sojourn to tolerate them and soften the hardships that accompany their wanderings. The Jewish church and nation are now dead. Once they were exalted to heaven, but now they are thrust down to Hadees, the kingdom of death, and the gulf that yawns between them and the Gentiles shall not be abolished till the fullness of the Gentiles shall come in, and “then Israel shall be saved.”

Lightfoot says: “The main scope and design of it seems this: to hint the destruction of the unbelieving Jews, who, though they had Moses and the prophets, did not believe them, nay would not believe though one (even Jesus) arose from the dead.”

Our quotations are not from Universalists, but from those who accepted the doctrine of eternal punishment, but who were forced to confess that this parable has no reference to that subject. The rich man, or the Jews, were and are in the same Hell in which David was when he said: “The pains of Hell (Hadees) got hold on me, I found trouble and sorrow,” and “thou hast delivered my soul from the lowest Hell.” Not in endless woe in the future world, but in misery and suffering in this.

But this is not a final condition. Wherever we locate it, it must end. Paul asks the Romans, “Have they (the Jews) stumbled that they should fall? God forbid! but rather through their fall salvation is come unto the Gentiles.” (Rom 11:11) and “For I would not, brethren, that ye should be ignorant of this mystery, lest you should be wise in your own conceits, that blindness is in part happened to Israel until the fullness of the Gentiles be come in, and so all Israel shall be saved. As it is written, There shall come out of Zion the deliverer, and shall turn away ungodliness from Jacob, for this is my covenant with them when I shall take away their sins.” (Rom 11:23-27)

In brief terms then, we may say that this is a fictitious story or parable describing the fate in this world of the Jewish and Gentile people of our Savior’s times, and has not the slightest reference to the world after death, nor to the fate of mankind in that world.

Let the reader observe that the rich man, being in Hades, was in a place of temporary detention only. Whether this be a literal story or a parable, his confinement is not to be an endless one. This is demonstrated in a two-fold manner:

1. Death and Hades will deliver up their occupants. Rev. 20:13

2. Hades is to be destroyed. 1 Cor. 14:55; Rev. 20:14

Therefore Hades is of temporary duration. The Rich Man was not in a place of endless torment. As Prof. Stuart remarks: “Whatever the state of either the righteous or the wicked may be, whilst in Hades, that state will certainly cease, and be exchanged for another at the general resurrection.”

Thus the New Testament usage agrees exactly with the Old Testament. Primarily, literally, Hades is death, the grave, and figuratively, it is destruction. It is in this world, and is to end. The last time it is referred to (Rev. 20:14) as well as in other instances (Hosea 13:14; 1 Cor. 15:55) its destruction is positively announced.

So that the instances (sixty-four) in the Old Testament, and (eleven) in the New; in all seventy-five in the Bible, all perfectly agree in representing the word Hell, derived from the Hebrew Sheol and the Greek Hades, as being in this world, and of temporary duration.

Note: This chapter is taken from J.W. Hanson’s “Bible Threatenings Explained” from 1883. Some points made by the author may not be perfectly in sync with modern scholarship.